First Lieutenant James Calhoun would have probably been another mostly forgotten Army officer of the past if it had not have been for the time and place he died: 25 June 1876 near the Little Bighorn River. Familiarly known as “Jimmi”, Lt. Calhoun was born in Ohio. Enlisting as a Private in February 1865 with the 22nd New York Infantry he was soon promoted to Sergeant in Co. D. In 1867, he was promoted to Second Lt. and served in the 32nd and 21st Infantries. Jimmi Calhoun met Maggie Custer, the general’s younger sister, at Fort Hays, Kansas in the summer of 1870.

Maggie dressed in white sitting on the left; Jimmi standing on the right. Taken at Fort Lincoln 1874.

Maggie dressed in white sitting on the left; Jimmi standing on the right. Taken at Fort Lincoln 1874.By August the couple was pressing General Custer to request Jimmi be transferred to the 7th Cavalry where he would be under Custer’s command. Jimmi got the transfer, and a promotion. First Lt. Calhoun and Maggie Custer were married in March 1872. Custer liked Calhoun enough personally and professionally to make him his adjutant which is the officer that handles correspondence and records. The 7th Calvary relocated to Fort Lincoln just south of Bismark, North Dakota. Jimmi’s unit took part in several Expeditions which protected railroad surveyors and pushed further into Indian territory to make way for Caucasian dominated settlements. The 7th Cavalry served under General David Stanley when it participated in Yellowstone Expedition (1873). A personal feud developed between General Stanley and General Custer. The feud came to a head when Stanley confronted Custer about the use of a government horse by a civilian correspondent. Custer was placed under arrest (later the charges were dismissed) and for two days rode at the rear of the column. The civilian was Jimmi’s brother Fred Calhoun.

Jimmi seated at a Fort Lincoln Staff Outing, 1875.

Jimmi seated at a Fort Lincoln Staff Outing, 1875.Jimmi was particularly suited to the task of adjutant. His writings were good enough to be formed into a book published in 1979 (Provo, Utah) edited by Lawrence Frost entitled With Custer in ’74. During the Black Hills Expedition (1874) Jimmi writes in his diary of July 2nd: “The air is serene and the sun is shining in all its glory. The birds are singing sweetly, warbling their sweet notes as they soar aloft. Nature seems to smile on our movement. Everything seems to encourage us onward.” Custer had surrounded himself with a “royal family” which included his own family members and Jimmi. Jimmi was the “blonde Adonis” of Custer’s staff. He was also the object of many jokes and pranks pulled on everyone in the family cluster. In Cavalier In Buckskin Robert Utley states “Calhoun, dour and humorless, was a favorite target.” The General himself mused, “ ‘How they do tease and devil Mr. Calhoun.’ “

Custer’s wife Libbie and her sister Maggie Calhoun often rode at the head of the cavalry column with their husbands while other wives traveled on an accompanying steamboat when the unit moved en masse. This is how they traveled the first day out of Fort Lincoln to start the new expedition west in May 1876. The first nights camp was on the Heart River about 13 miles west from Bismark. The wives returned to Fort Lincoln the next morning. These expeditions were always dangerous and Jimmi wrote of how Indian alarms denied sleep to all. Violent death was always a hazard that happened regularly, but not to the extent that became “Custer’s Last Stand”.

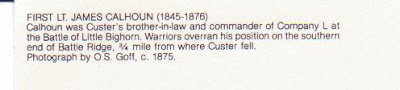

The Last Stand has been researched and argued about by professional and amateur historians on a scale that reminds one of the JFK assassination. In Archaeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle Richard Fox calls the “Calhoun Episode” the most critical stage of the Custer battle. Jimmi commanded L Company. They were apparently the first attacked and had been left to form a rear skirmish line on one hill which defended Custer as he rode about one mile further to die on his own hill. Today in the Little Bighorn National Park they are named Custer Hill and Calhoun Hill. Eyewitness reports from the Native Americans conferred that the attackers encountered the most resistance and suffered the most casualties at Calhoun Hill. About 31 men were killed on Calhoun Hill. Hasty burial parties were formed to dig graves for the officers-enlisted men lay where they fell. Recovery of the bodies weren’t attempted until a year later in July 1877. Jimmi was re-interred at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. One of the original burial party members was William Taylor who composed a book, With Custer On The Little Bighorn. In a section titled “Relics of the Battle” with no other explanation he states: “Mrs. James Calhoun had the good fortune to obtain possession of her husband’s watch through the efforts of her brother-in-law Lt. Calhoun, who purchased it from some Indians in the Dept. of the Platte.” Apparently Fred joined the Army between the time of the Stanley incident and the death of his brother.

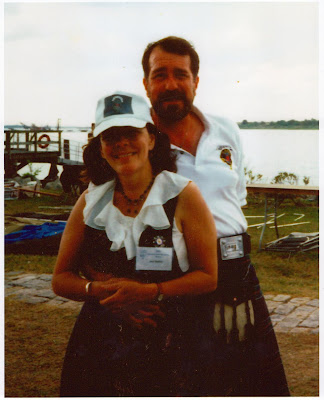

Jimmi and Maggie had no children that I could find recorded anywhere. We had the good fortune for Glen Ethier and 8 other volunteers to index all four volumes of Orval Calhoun’s Our Calhoun Family a few years ago (this index is available directly through the Clan Colquhoun Society of NA, Glen himself, or access it through the Odom Genealogical Library in Moultrie). I ran Jimmi and Fred’s name, and the name Custer through the search engine but found nothing there. General Custer’s widow, Libbie, made a career out of remembering and having other people take note of her husband. In Boots And Saddles, one of the books Libby Custer wrote about her husband, Jane Stewart notes in her Introduction that there is a “noticeable omission” by Mrs. Custer to identify almost any of the other officers of the 7th Cavalry. Jimmi Calhoun is “…casually referred to as ‘Margaret’s husband.’ “

Above: Maggie on the right sitting next to Jimmi.

Above: Maggie on the right sitting next to Jimmi.Below: Lt. Fred Calhoun with his legs crossed. Libbie and George Custer above him. Taken on the steps of the Custer home in 1873.